OHNY 2006 — Part I

We emerged into the bright sunlight from the pleasantly disorienting (de)tour of the Ramble, and exited the East side of the Park on 79th Street, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

At the intersection, we paused to admire the stunning French Renaissance limestone mansion across the street: a regal, lacy form of ornate arches, Gothic moldings, high mansards and fantastical pinnacles. I gazed up, fantasizing about who would live in such a grand house.

As we turned the corner, en route to the Lexington line, we discovered that the current occupant of the mansion is not an extremely wealthy family, but, in fact: The Ukrainian Institute of America. Their website has some fuller images of the mansion exterior in all its glory.

As serendipity would have it, the UIA was also a participant in the openhousenewyork weekend: “America’s largest architect and design event,” opening doors around the city for the fourth year in a row.

We popped inside just as the Director’s tour was beginning on the second floor. An assembled crowd of about a dozen people were gathered around him in the stately gallery, as he explained some of the history surrounding the 1899 house, originally known as the “Isaac and Mary Fletcher House,” now landmarked as the “Harry F. Sinclair House.” Financier and art collector Isaac D. Fletcher commissioned architect Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert — usually referred to in architectural sources as C. P. H. Gilbert — to build a house using William K. Vanderbilt‘s Loire Valley chateau as its model, on the property which was originally the Lenox farm. Gilbert designed mansions for many of the leading families of New York, including several homes on “Millionaire’s Row,” and in Park Slope. Also a suite of townhouses at 72nd Street and Riverside Drive and the Joseph R. DeLamar mansion at 37th Street and Madison – now home to the Polish Consulate.)

The Fletcher/Sinclair mansion was purchased by oil industrialist (and Teapot Dome scandal-ridden) Harry F. Sinclair in 1920, and in 1930 was taken over by eccentric bachelor and recluse Augustus Van Horn Stuyvesant (the last direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant to bear his surname.) In 1955, the mansion was purchased for use by the Ukrainian Institute of America corporation by William Dzus, prominent Ukrainian inventor, industrialist, philanthropist and founder of the Institute.

Carved woodwork on the broad staircase – just one of the many refined touches throughout the house’s six floors (only three of which were open for public viewing.)

Mary Fletcher’s elegant oval dressing room:

Call box for the mansion’s many servants, located on a wall of what was the first-floor kitchen — now used for the Institute’s adminstrative offices:

Throughout the year, the Institute hosts a variety of private and public events, including art exhibits, classical and modern music programs, lectures, readings, seasonal celebrations and special events. Other sources of income include rental of the space for movie and television shoots. According to the Director, upkeep and maintenance of the property runs upwards of $400,000 per year, not including taxes (which as a non-profit, the Institute does not pay.)

After a brief stop for breakfast sandwiches at the nearby Hot & Crusty, we hopped the 6 down to Grand Central, to hit stop #2 on our OHNY 2006 tour: the world famous Chrysler Building. Despite passing by too many times to count, I’d not actually set foot inside this landmark in perhaps 15 years.

Long considered one of New York City’s most glorious and distinctive skyscrapers, The Chrysler Building, on Lexington Avenue at 42nd Street is a famous example of Art Deco architecture. It was completed in the Spring of 1930 for the Walter P. Chrysler car manufacturing company. The distinctive ornamentation (most notably: the famous hood-ornament eagles, whose sleek heads extend from eight corners on the building’s 61st floor) are based on features that were then being used on Chrysler automobiles.

Most people are familiar with at least some of the interesting history of the building: how Brooklyn-born architect William Van Alen found himself in ardent competition with his former partner, H. Craig Severance (architect of the Bank of Manhattan at 40 Wall Street), for top “World’s Tallest Building” honors; how the matter was settled definitively in Van Alen’s favor when he erected his secret (and secretly pre-assembled) weapon in just 90 minutes on October 23, 1929: the 27-ton, 180-foot sunbursted steel spire; how the building held the “World’s tallest” title for just a few months before the Empire State Building surpassed it. No need to retread much here.

Ultimately, the construction of the Chrysler Building ended being more a curse than a boon for its architect. Most critics scorned the building as a gauchely oversized vanity project with little architectural merit. And by the time the building was officially opened on May 27, 1930, Van Alen himself had run into serious difficulties: accusations of corruption and contractor bribery and, much worse, a bill dispute with Chrysler, who refused to pay his full, percentage-based, fee. It was only after a lengthy court battle that Van Alen managed to obtain sufficient compensation. Although history would immortalize Van Alen for his masterpiece, he had lost his good reputation as an architect and never worked on a notable commission again.

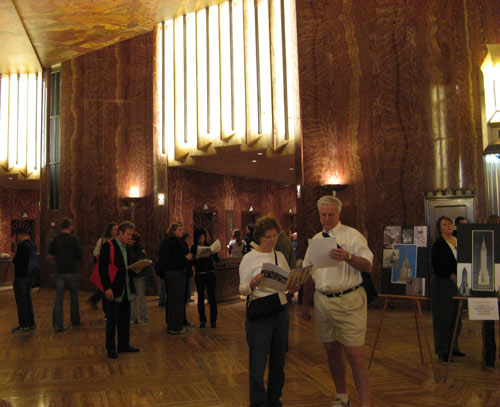

The building no longer maintains a public viewing gallery on the 71st floor, but we were allowed to wander around the stunning 3-story triangular Art Deco lobby with its lavishly decorated with polished Red Moroccan marble walls and multi-hued marble, travertine and onyx floors.

All of the building’s 32 elevators are lined in a different pattern of wood marquetry, using eight varieties of wood from four continents.

Burnished steel stairwell with Art Deco chrome banister:

Detail of the elaborate ceiling mural, “Energy, Result, Workmanship and Transportation,” painted by Edward Trumbull. At some 70 by 100 feet, it was the largest in the world upon its completion.

To be continued…

There's 1 comment so far ... OHNY 2006 — Part I

Those buildings really were incredible.

Go for it ...

Search

Popular Tags

Categories

Archive

- July 2010

- July 2009

- January 2009

- November 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

October 14, 2006